To view the original Medscape article, click here.

During March 2012, an unusual cluster of postprocedural cases of endophthalmitis was first noticed at an ambulatory surgical center in California.[1] Collaboration between CDC, state and local health departments, and the US Food and Drug Administration led to the identification of 43 cases of fungal endophthalmitis in 9 states. Twenty-one of these cases were found to be associated with intravitreal injections of Brilliant Blue-G, a dye most commonly used to visualize the retinal membrane during intraocular surgery. The remaining 22 cases were associated with intravitreal injections of a steroid called triamcinolone, commonly used to reduce intraocular inflammation. Both products were labeled as sterile and came from a single compounding pharmacy in Florida. The compounding pharmacy recalled the contaminated products and is no longer producing sterile compounded substances.

Hello. I’m Dr. Rachel Smith, an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer in the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). I’m pleased to speak with you about fungal endophthalmitis today as part of the CDC Expert Video Commentary Series on Medscape.

Endophthalmitis, an inflammation in the intraocular cavities of the eye, can be caused by many pathogens, including bacteria and fungi. Bacterial endophthalmitis is most common. Fungal endophthalmitis, although much rarer, often is not diagnosed until a patient fails to improve on antibacterial therapy, and it can result in devastating vision loss.

Two types of endophthalmitis can occur. Exogenous fungal endophthalmitis occurs after fungal spores enter the eye from an external source, such as a contaminated irrigation solution, injection, intraocular lens implant, or piece of surgical equipment. Most cases of exogenous endophthalmitis occur as a complication of eye surgery or other invasive eye procedures, such as intravitreal injections. Exogenous endophthalmitis in general is very rare, occurring as a complication of cataract surgery in less than 0.1% of patients and 0.04% of intravitreal injections or vitrectomies.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is even less common than the exogenous form, accounting for only 2%-15% of all cases of endophthalmitis.[2] Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis occurs when a fungal bloodstream infection spreads to one or both eyes. Most commonly, fungal endogenous endophthalmitis occurs in patients with candidemia, a Candida bloodstream infection.

The Mycotic Diseases Branch of CDC is working to understand and prevent episodes of both types of fungal endophthalmitis. In 2005, an investigation was launched into a large outbreak of fungal keratitis and exogenous endophthalmitis affecting more than 160 persons in multiple countries. These ocular infections were found to be associated with soft contact lens wear and a specific brand of contact lens solution. Evaluating endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Candida species is a part of a larger population-based candidemia surveillance system run by the Mycotics Diseases Branch with the Emerging Infections Program in multiple cities across the United States.

Fungal endophthalmitis can be difficult to diagnose. Although it can resemble a bacterial infection in its initial presentation, with pain, reduced vision, swelling, and redness in the affected eye, developing days to weeks after exposure, it can also present as an indolent, subacute infection with waxing and waning visual acuity and without a large pain component. Combined with the rarity of fungal endophthalmitis, this makes it challenging for clinicians to recognize the infection when it occurs. Fungal endophthalmitis should be considered if a patient has a persistent eye infection that is not responding to initial antibacterial treatment. Diagnosis is made through culture of vitrectomy cassette fluid, so it is important to order a fungal culture when fungal endophthalmitis is suspected.[3]

Fungal endophthalmitis should be treated by a retinal specialist because it can lead to permanent vision loss if it is not treated quickly and correctly. The infection should be treated with antifungal medication administered intravitreally and/or systemically.[4] Consultation with an infectious disease specialist may be necessary for assistance in choosing appropriate type and route of antifungal medication. Patients may also need to undergo a vitrectomy, a surgery to remove some or all of the vitreous gel from the interior of eye. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment may lead to better outcomes; therefore, maintaining a high index of suspicion for these infections is very important.

All clinicians should consider fungal endophthalmitis when diagnosing a persistent or progressive eye infection if the patient has any of these risk factors:

- Recent eye surgery or other invasive eye procedure;

- Recent eye injury;

- Diabetes;

- Steroid use;

- Immunosuppression; or

- Fungal bloodstream infection such as candidiasis.

Urgent referral to a retinal specialist is indicated if fungal endophthalmitis is suspected.

Ophthalmologists who perform invasive eye procedures can take preventive measures, including:

- Evaluating patient risk factors before performing an invasive eye procedure;

- Monitoring postprocedure or eye trauma patients closely for signs of infection; and

- Educating patients about the signs and symptoms of endophthalmitis and when to seek help.

Finally, cases of fungal endophthalmitis should be reported to local or state public health departments for further investigation if they are part of a suspected cluster of cases or related to a contaminated product or instrument.

Thank you.

Rachel M. Smith, MD, MPH, is an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer with the Mycotic Diseases Branch, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Smith received her bachelor’s degree and MPH at the University of California, Berkeley. She the completed her MD, followed by her clinical rotations in internal medicine, at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Smith joined the CDC in 2011.

Medical and Patient education videos

-

Title

Description

-

I have Sarcoidosis, Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CPA) and a very low CD4 count. I have challenged myself to do a daily vlog for 30 days

Follow me on twitter @StewArmstrong

Here is the link for all of the monthly aspergillosis meetings http://www.nacpatients.org.uk/monthly…

This meeting was for July 2016.

Aspergillus Website: Follow all of our Youtube collections here

-

Stewart Armstrong has chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and has undertaken to record a video of every day of his life for a month in order to help raise awareness of aspergillosis and how it impacts their daily lives.

These videos are interesting for a number of reasons – not least because patients often say that they don’t look unwell so many people don’t understand how serious aspergillosis is. Does Stewart look or act unwell?

See the month of vlogs in the playlist below, or go to Stewart’s YouTube page to watch more of his videos.

-

Global fungal killers and life-threatening infections

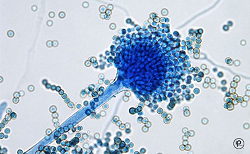

Fungi are everywhere, and a few species can cause very serious lethal infections. Fungal infections

-

This panel considers and debates one of the greatest obstacles to food security in many parts of the world: mycotoxin. Aflatoxin is a particularly dangerous mycotoxin produced predominantly by two Aspergillus fungi. It colonizes a variety of important food and feed crops both pre- and post-harvest, including groundnuts, tree nuts, maize, rice, figs and other dried foods, spices, crude vegetable oils and cocoa. Contaminated crops have significant health risks for both humans and animals, having been linked to retarded growth and development (stunting), immunosuppression and liver cancer. The aflatoxin issue has other, complex implications for food security and, by limiting farmers’ access to international markets, can lead to food waste and economic instability.

Panelists:

-John Lamb, Principal Associate, Abt Associates

-Dr. Kitty Cardwell, National Program Leader, USDA-NIFA

-Barbara Stinson, Senior Partner, Meridian Institute; Project Director, Partnership for Aflatoxin Control in Africa

-Moderator: Dr. Howard-Yana Shapiro, Chief Agricultural Officer, Mars, Incorporated -

The role of poorly maintained ventilation ductwork in spreading airborne infections is largely ignored because it is ‘out of sight out of mind’, but recent analysis by healthcare professionals confirms that the risks are increasing.

Ghasson Shabha will identify particular threats in healthcare facilities from dirty ductwork. He also points out that fewer than 5% of building air-conditioning systems have been inspected despite regulations making this mandatory. Dr Shabha will look at how planned cleaning strategies can reduce risks and how hospitals can use 3D building information modelling software to identify ‘infection hotspots’.

The healthcare environment can be described as a reservoir for potentially infective agents which can spread unpredictably in a whole array of ways particularly in ventilation and air-conditioning systems making it difficult to effectively control and manage, for those seeking timely information about the patterns of cross-infection. The severity of the problem has been highlighted extensively over the past decade, as part of wider umbrella of what was known as health care acquired infections (HCAIs). Airborne transmission extends over a wide spectrum, and includes many prevalent agents, inter alia Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB),nosocomial MRSA, Aspergillus fumigatus, Serratia marcescens, norovirus, and other airborne infection.

Dr Shabha was speaking live from Birmingham and this CIBSE ASHRAE Group (cibseashrae.org) webinar was co-sponsored by the B&ES Ventilation Hygiene Group and the Institute of Healthcare Engineering and Estate Management (IHEEM).

-

Oliphant Science Awards – Year 1 project by Haruki Kurioka, Aleksa Novakovic and Bogdan Novakovic (St Andrew’s Primary School, Adelaide)

Food that we consume daily is rich in good bacteria and fungi. Yogurt, Yakult and Natto (fermented soybeans) are rich in bacteria. Cheeses (e.g. Brie & Blue cheese) and Koji contain fungi Penicillium and Aspergillus, respectively. Many Japanese and continental seasonings and dishes can be prepared with those products. Many kids and their parents don’t know much about good bacteria and fungi. First year students are here to tell us their story. Enjoy it!