To view the original Medscape article, click here.

During March 2012, an unusual cluster of postprocedural cases of endophthalmitis was first noticed at an ambulatory surgical center in California.[1] Collaboration between CDC, state and local health departments, and the US Food and Drug Administration led to the identification of 43 cases of fungal endophthalmitis in 9 states. Twenty-one of these cases were found to be associated with intravitreal injections of Brilliant Blue-G, a dye most commonly used to visualize the retinal membrane during intraocular surgery. The remaining 22 cases were associated with intravitreal injections of a steroid called triamcinolone, commonly used to reduce intraocular inflammation. Both products were labeled as sterile and came from a single compounding pharmacy in Florida. The compounding pharmacy recalled the contaminated products and is no longer producing sterile compounded substances.

Hello. I’m Dr. Rachel Smith, an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer in the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). I’m pleased to speak with you about fungal endophthalmitis today as part of the CDC Expert Video Commentary Series on Medscape.

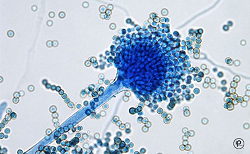

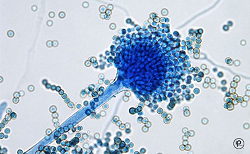

Endophthalmitis, an inflammation in the intraocular cavities of the eye, can be caused by many pathogens, including bacteria and fungi. Bacterial endophthalmitis is most common. Fungal endophthalmitis, although much rarer, often is not diagnosed until a patient fails to improve on antibacterial therapy, and it can result in devastating vision loss.

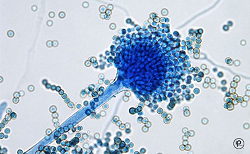

Two types of endophthalmitis can occur. Exogenous fungal endophthalmitis occurs after fungal spores enter the eye from an external source, such as a contaminated irrigation solution, injection, intraocular lens implant, or piece of surgical equipment. Most cases of exogenous endophthalmitis occur as a complication of eye surgery or other invasive eye procedures, such as intravitreal injections. Exogenous endophthalmitis in general is very rare, occurring as a complication of cataract surgery in less than 0.1% of patients and 0.04% of intravitreal injections or vitrectomies.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is even less common than the exogenous form, accounting for only 2%-15% of all cases of endophthalmitis.[2] Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis occurs when a fungal bloodstream infection spreads to one or both eyes. Most commonly, fungal endogenous endophthalmitis occurs in patients with candidemia, a Candida bloodstream infection.

The Mycotic Diseases Branch of CDC is working to understand and prevent episodes of both types of fungal endophthalmitis. In 2005, an investigation was launched into a large outbreak of fungal keratitis and exogenous endophthalmitis affecting more than 160 persons in multiple countries. These ocular infections were found to be associated with soft contact lens wear and a specific brand of contact lens solution. Evaluating endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Candida species is a part of a larger population-based candidemia surveillance system run by the Mycotics Diseases Branch with the Emerging Infections Program in multiple cities across the United States.

Fungal endophthalmitis can be difficult to diagnose. Although it can resemble a bacterial infection in its initial presentation, with pain, reduced vision, swelling, and redness in the affected eye, developing days to weeks after exposure, it can also present as an indolent, subacute infection with waxing and waning visual acuity and without a large pain component. Combined with the rarity of fungal endophthalmitis, this makes it challenging for clinicians to recognize the infection when it occurs. Fungal endophthalmitis should be considered if a patient has a persistent eye infection that is not responding to initial antibacterial treatment. Diagnosis is made through culture of vitrectomy cassette fluid, so it is important to order a fungal culture when fungal endophthalmitis is suspected.[3]

Fungal endophthalmitis should be treated by a retinal specialist because it can lead to permanent vision loss if it is not treated quickly and correctly. The infection should be treated with antifungal medication administered intravitreally and/or systemically.[4] Consultation with an infectious disease specialist may be necessary for assistance in choosing appropriate type and route of antifungal medication. Patients may also need to undergo a vitrectomy, a surgery to remove some or all of the vitreous gel from the interior of eye. Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment may lead to better outcomes; therefore, maintaining a high index of suspicion for these infections is very important.

All clinicians should consider fungal endophthalmitis when diagnosing a persistent or progressive eye infection if the patient has any of these risk factors:

- Recent eye surgery or other invasive eye procedure;

- Recent eye injury;

- Diabetes;

- Steroid use;

- Immunosuppression; or

- Fungal bloodstream infection such as candidiasis.

Urgent referral to a retinal specialist is indicated if fungal endophthalmitis is suspected.

Ophthalmologists who perform invasive eye procedures can take preventive measures, including:

- Evaluating patient risk factors before performing an invasive eye procedure;

- Monitoring postprocedure or eye trauma patients closely for signs of infection; and

- Educating patients about the signs and symptoms of endophthalmitis and when to seek help.

Finally, cases of fungal endophthalmitis should be reported to local or state public health departments for further investigation if they are part of a suspected cluster of cases or related to a contaminated product or instrument.

Thank you.

Rachel M. Smith, MD, MPH, is an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer with the Mycotic Diseases Branch, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Smith received her bachelor’s degree and MPH at the University of California, Berkeley. She the completed her MD, followed by her clinical rotations in internal medicine, at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Smith joined the CDC in 2011.

Medical and Patient education videos

-

Title

Description

-

Dr. Rohini Manuel, Consultant Clinical Microbiologist, Public Health England, London

-

Shila Seaton, Bacteriology Scheme Manager, UK NEQAS for Microbiology, Public Health England

-

Dr. P. Lewis White, Principal Clinical Scientist, Public Health Wales Microbiology, Cardiff

-

Prof. Dr. Clemens Decristoforo, Radiopharmacist, Univ.Klinik f.Nuklearmedizin, Innsbruck, Austria

-

Dr. Martin Hoenigl, Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Austria

-

Dr. Jonathan Lambourne, Consultant in Infectious Diseases, Barts Health NHS Trust, London

-

Dr. Inês Ushiro-Lumb, Lead Clinical Microbiologist for Organ Donation and Transplantation, NHS Blood and Transplant, London

-

Dr. Mike Bromley, Lecturer, Institute of Inflammation and Repair, University of Manchester

-

Dr. Sharleen Braham, Clinical Scientist, King’s College Hospital, London

-

Dr. Duncan Wilson, Research Fellow, Aberdeen Fungal Group, University of Aberdeen