Submitted by GAtherton on 21 July 2016

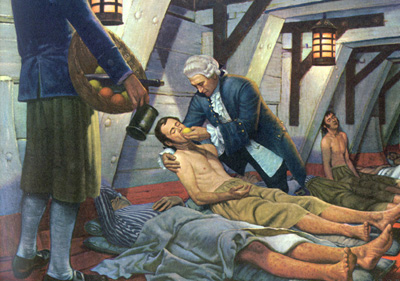

and their juices would cure and prevent scurvy, the disease which killed a million seamen between

1600 and 1800. In this painting he is shown aboard H.M.S. Salisbury in 1747. (From A History of

Medicine in Pictures, Parke, Davis and Co., copyright 1960. Artist Robert Thom.)

First developed in 1747 by James Lind, physician to the Royal Navy Random Controlled Trial’s (RCT) have been the backbone of of drug development and testing. Lind tested the effect of lime juice on the occurrence of scurvy on Royal Navy ships – a major health problem on long voyages. Crucially Lind randomised which of his patients received the treatment (lime juice plus several other liquid tested) and which did not, thus removing any (conscious or unconscious) bias in his experiments and radically improving the statistical significance and robustness of the conclusions. It didn’t matter that he knew nothing of the vitamin C contained in lime juice, he successfully deduced from his results that lime juice could ‘cure’ scurvy.

Modern trials are more sophisticated and there are several types but all follow the same principle of randomising which patient is treated with an active drug and which an inactive control. The best trials go further such that neither patient or dispensing doctor knows which is the active drug (double blinding) so there can be no bias caused by a patient unobjectively reporting their symptoms or a doctor recording the results in a similar subjective manner.

Conventional RCTs are usually conducted following strict inclusion criteria, which often exclude those patients with other multiple conditions. The Salford Lung Study (SLS) was designed to include those patients who would often be excluded from a traditional randomised trial, for example individuals also being treated for other chronic diseases. This inclusive approach is important because it is more realistic of everyday practice and is therefore representative of a much wider patient population. More patient representation should pick up more ‘real world’ experiences for use of the test drug and thus provide much more information on what happens when the drug is used in patient groups for which a traditional trial would not be designed – the market for sale of the drug will also presumably be larger more quickly so there are clear benefits for the pharmaceutical companies too!

Conventional RCTs are usually conducted following strict inclusion criteria, which often exclude those patients with other multiple conditions. The Salford Lung Study (SLS) was designed to include those patients who would often be excluded from a traditional randomised trial, for example individuals also being treated for other chronic diseases. This inclusive approach is important because it is more realistic of everyday practice and is therefore representative of a much wider patient population. More patient representation should pick up more ‘real world’ experiences for use of the test drug and thus provide much more information on what happens when the drug is used in patient groups for which a traditional trial would not be designed – the market for sale of the drug will also presumably be larger more quickly so there are clear benefits for the pharmaceutical companies too!

Part of the requirement to be able to carry out such a trial design was that patient records were quickly and easily accessible via their electronic health records. The provision of electronic health records throughout the NHS has had a flawed recent history but progress is being made steadily, albeit often locally rather than nationally. Perhaps then the tools to carry out this new trial design will be widely available quite soon, though SLS design is not an end in itself yet as in this case a more traditional, less inclusive trial ran alongside SLS. The data provided by SLS will complement the existing data provided by the conventional RCT.

Part of the requirement to be able to carry out such a trial design was that patient records were quickly and easily accessible via their electronic health records. The provision of electronic health records throughout the NHS has had a flawed recent history but progress is being made steadily, albeit often locally rather than nationally. Perhaps then the tools to carry out this new trial design will be widely available quite soon, though SLS design is not an end in itself yet as in this case a more traditional, less inclusive trial ran alongside SLS. The data provided by SLS will complement the existing data provided by the conventional RCT.

News archives

-

Title

Date