Submitted by GAtherton on 22 November 2016

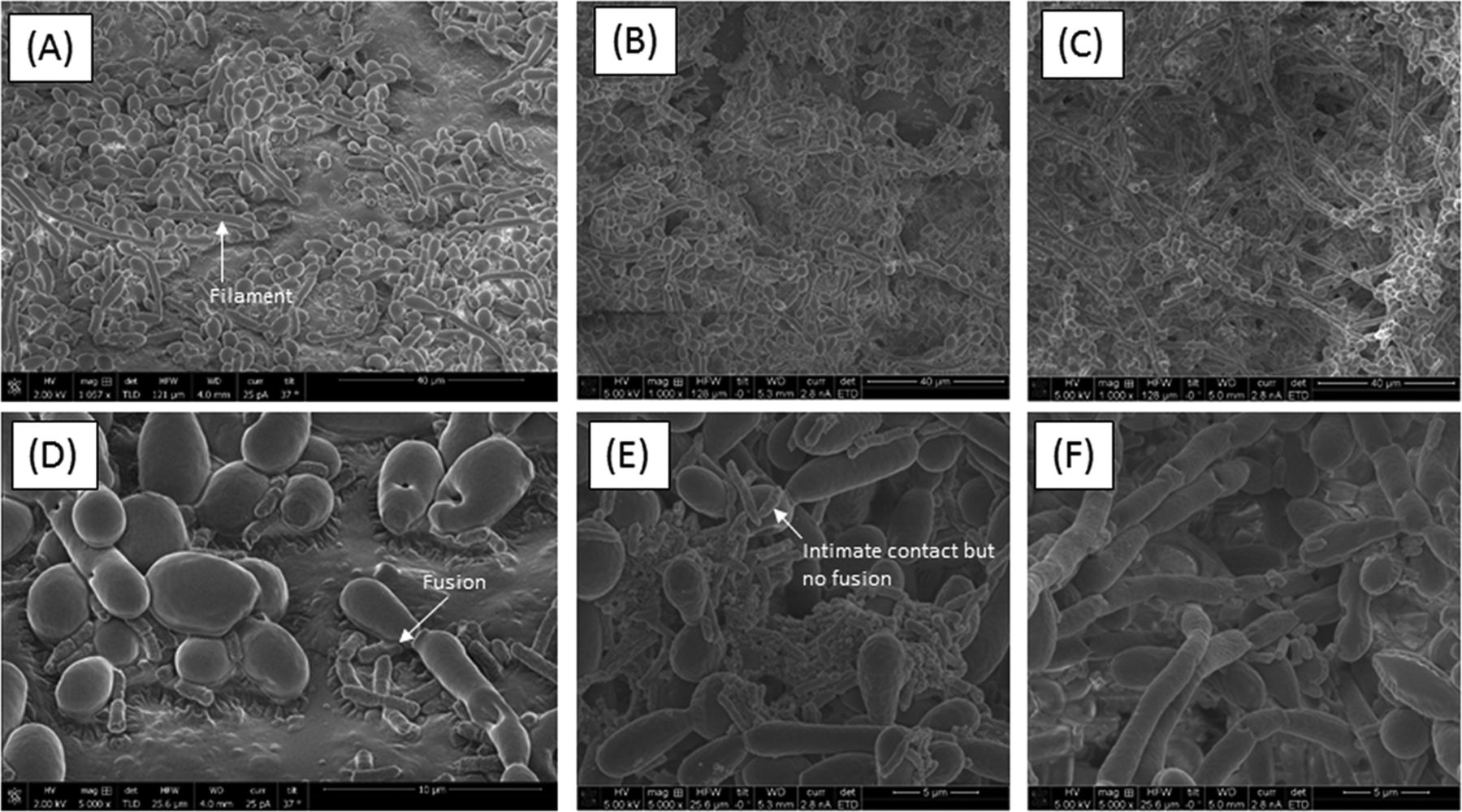

Microbial biofilms are a relatively recently studied phenomenon in relation to pathogenic fungi. Much has already been learned about which fungal species produce biofilm and how resistant they become to attempts to kill or control the fungus particularly when they coat implanted medical devices. Initially yeasts such as Candida were discovered to be biofilm producers but it quickly became apparent that other fungi also grew biofilms including Aspergillus fumigatus.

A. fumigatus is particularly interesting because it is also a good example of a fungus that produced biofilm irrespective of it growing on a hard surface such as a medical device. A. fumigatus produces a growth state resembling biofilm during infection of lung tissue with hyphae embedded in an extracellular matrix. The study of lung infection by this fungus must therefore mimic this growth form if we are to fully understand and hopefully successfully treat such infections – and that is precisely what has been achieved by Gibbons et.al 20121. It has emerged that many pathogenic fungi form biofilms and that the biofilms somehow protect the fungi from attack by antifungal drugs and make infection difficult to control. Clearly attacking the biofilm itself with a future generation of drugs or other forms of treatment is a priority.

More recently a new article written for the American Society of Microbiology summarises the findings of new research moving us away from looking at what single species do in isolation and towards something more complex but better reflecting the natural world where multiple microbial species inhabit the same space and compete for the same limiting resources – but also have a common need to protect themselves from attackers.

Experiments show that when Candida is grown in a mixed culture with bacterial Serratia or Escherichia species it takes on a biofilm-like hyphal growth form whereas when it is growth in isolation it resembles much more closely the familiar Candida yeast form. Only the former is associated with its pathogenic, destructive activities, so it appears that in order to fully assess the pathogenicity of this Candida species co-cultivation with bacteria is required. It is apparent that Candida requires co-cultivation with bacteria in order to become fully pathogenic.

Perhaps here is a hint as to why many people who have Crohnes disease tend to have particular mixtures of microbes in their gut – perhaps the mixtures of microbes promote the inflammation? This has important implications for future research into treating this disease.

Candida clearly benefits from growing with Serratia & Escherichia in a biofilm. What do the bacteria get out of their collaboration with the fungus? It appears that they can gain protection from antibiotics as if the bacteria are cultured within the biofilm produced by the fungus they become more resistant to antibiotics. Interspecies collaboration goes both ways as you might expect – if they didn’t they would be unlikely to persist for long.

Clearly future studies on breaking through antifungal drug resistance and fully understanding the pathogenicity of fungi must include studies of how biofilms influence and mediate those properties of pathogens such as Aspergillus and Candida – and quite possibly reveal vital information on how we approach treatment of a whole host of other diseases too.

Resources referred to

1. Gibbons JG, Beauvais A, Beau R, McGary KL, Latge JP, Rokas A. 2012. Global transcriptome changes underlying colony growth in the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 11: 68–78 Paper

Original Article written for ASM

News archives

-

Title

Date